One Label Under Blackmail: PART 2

Diddy And The Epstein Network

Moving Uptown

Following his graduation from Mount St. Michael Academy, Combs enrolled at the prestigious Howard University in Washington, DC to study business in 1987. He promptly set about further inflating his street cred as he expanded his horizons into a new popularity-maximizing enterprise –– party planning and promotion. His parties were described by classmates as offering a “once-in-a-lifetime type of vibe” and Combs spared no expense in spreading the word, driving around campus in his convertible to pass out fliers for events. Author Susan Traugh wrote that some of Combs’ collegiate parties attracted thousands of guests.

Comb’s entrance onto the hip hop scene began during his freshman year when Combs scored a side-gig as rapper-beatboxer Doug E. Fresh’s valet, where he “shuttl[ed] Fresh’s clothes to and from the dry cleaner in his Volkswagen Rabbit convertible.”vii All the while, Combs organized parties in and around the Beltway as well as back home in New York City on the weekends. He was also a background dancer in one of Fresh’s music videos around this time.

While at Howard, the darker, predatory side of Combs’ reputation also began to take shape, with accusations of belligerence, sexual harassment, and domestic violence following in his wake. Contemporaneous accounts provided by sources to Rolling Stone tell of Combs beating a girlfriend with his belt in full view of the public on the Howard quad. Another time, he tapped on the glass window of an English class in session to try and coax a woman into skipping. On another occasion, he non-consensually caressed a woman’s back and asked her if he could introduce her to “one of his friends.”

By age 20, Combs had begun focusing more of his attention on his nascent internship and career at Uptown Records, a job he had first secured in 1990 via his Mount Vernon neighbor, the rapper Heavy D. Combs’ initiative soon saw him become former Def Jam recordman Andre Harrell’s intern. He commuted from Howard to NYC via Amtrak in the mornings, stowing away in the bathroom to avoid paying fare. He also shadowed party promoter Jessica Rosenblum during the planning stages for Heavy D’s platinum-album celebration. Rosenblum “obliged his requests to take him to all the ‘freaky’ nightspots on the Lower East Side.”viii Rosenblum takes credit for having introduced Combs to some of the biggest names among NY scenesters and club kids — as well as updating his eyewear fashion. Rosenblum graduated from her hip hop party promoter career to become a NYC interior designer wedded to Steve Young, head of global litigation for one of the Big 4 Accounting firms, Ernst & Young.

In the late 1980s, while still a student at Howard, Combs learned that Uptown Records’ A&R (artists and repertoire) executive had vacated the company. Combs took his boss Andre Harrell out to lunch to press for the job and, after a successful schmooze, soon transformed himself into one of the youngest talent scouts in the industry.ix Combs later told Rolling Stone that, after joining Uptown, “Andre became like my big brother. He bought a mansion, gave me a room [. . .] Not a mansion, a big house. It was a mansion to me, though, and he had gave [sic] me a room in the house.”

Uptown’s Secret to Success: Andre Harrell & MCA

Prior to his mentorship of Sean Combs, Uptown’s Andre Harrell first broke into the nascent hip hop industry by way of his rap duo Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde, which he and a friend had formed in high school. Harrell withdrew from Lehman College in 1983 to focus on his career as an account executive selling airtime for New York all-news AM station WINS. WINS was previously owned by radio pioneer J. Elroy McCaw, an ex-OSS agent and member of the Advisory Council to the US National Security Council.x McCaw hired trailblazing disc jockey Allan Freed to man the mic at the station, a deal that was brokered by record executive Morris Levy.xi

Per Potash, a US Assistant Attorney later claimed that Levy’s jazz label Roulette Records, boosted by his relationship with WINS’ Freed –– the most popular DJ in the country in the 1950s and 1960s –– was a “way station for heroin trafficking.” Levy and Roulette were also linked to organized crime, specifically the Genovese crime family. Levy was notably the main financier behind the first hip hop record label, Sugar Hill. The zenith of Freed’s celebrity was exemplified by Paramount Pictures hiring him at a rate of $29,000 per day to make a teen movie in 1957. Shortly thereafter, Freed was targeted by a smear campaign, resulting in him being unceremoniously and inexplicably fired by McCaw in 1958. Freed was singled out by Orrin Hatch’s Congressional committee during the first “payola” scandal involving the bribing of radio stations in return for singles plays. As a result, Freed became the face of the scandal, his career in shambles. As Potash writes regarding Freed’s downfall, “Morris Levy, the source of much of the payola bribe money, was never called to testify.”xii

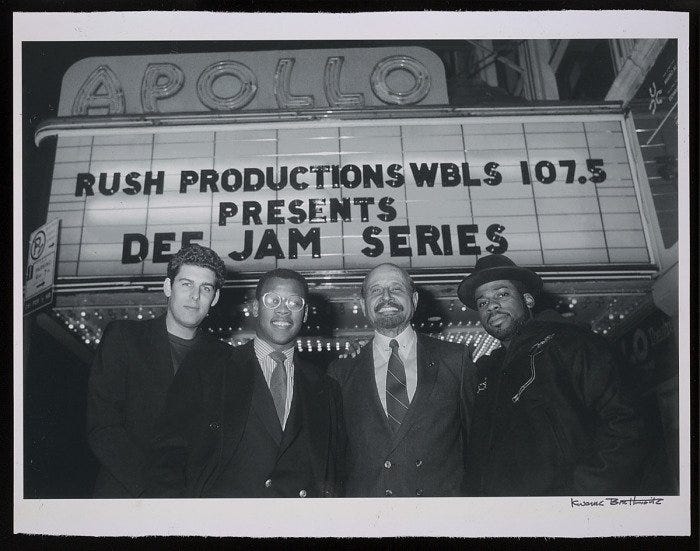

Months after joining WINS, Harrell’s job prospects experienced a dramatic upswing when he met Russell Simmons, co-founder of the Def Jam record label, who would later become very close to Sean Combs. Simmons soon offered Harrell a job with Def Jam. Within two short years (a rapid ascent mirroring Combs’ own), Harrell worked his way up to VP and general manager of the label. Def Jam’s early success was due in part to its 1984 distribution deal with CBS and its subsidiary Columbia Records. At the time, the label was run by Walter Yetnikoff, a close associate and friend of Clive Davis –– the man who would later become Sean Combs’ second mentor after Harrell that is a later focus of this piece. Appointed by Paley, Yetnikoff is heavily implicated in the Payola scandals of the 1980s that involved the “independent promotion” syndicate known as The Network, for which CBS Records was one of the biggest clients.xiii Yetnikoff went to some ends to protect the established payola system, firing his deputy president Dick Asher in 1983 and, per UPI, even quashing an investigation by the Recording Industry Association of America. By 1986, CBS Records had come under the control of Laurence Tisch, the billionaire head of Loews Corporation and a founding member of the Leslie Wexner and Charles Bronfman-brokered “Mega Group.”

Harrell’s success in management, contrary to music-making, seemed to have clarified things for Harrell, as his short-lived stint as a Profile Records artist came to a close when his high school rap duo with Alonzo Brown split up in 1986. That same year, Harrell struck out on his own to create Uptown.

However, before leaving Def Jam, Harrell was responsible for Def Jam’s hiring of Israeli-American Lyor “Little Lansky” Cohen, who would later force out Def Jam co-founder Rick Rubin in order to co-run the label with Simmons. Years later, upon leaving Def Jam, Cohen would team up with the family who had taken control of Def Jam in the 1990s, the Bronfmans, to become the top executive at Warner Music, an event that will be revisited in Part II of this series.

Not unlike Def Jam, Uptown’s early success (and the furtherance of Harrell’s career in the industry) was due to its distribution deal with a major entertainment conglomerate. In Uptown’s case, the company in question was the Music Corporation of American (MCA), an entertainment giant that dominated the American music and movie industry for many decades. Uptown’s early distribution deal with MCA began in 1987 and soon expanded into a formal partnership with the company a year later in 1988. Their ties grew even deeper in 1992, when MCA offered Uptown a $50 million deal whereby Uptown expanded into film and television.

In a Vanity Fair obituary for Andre Harrell, screenwriter and journalist Barry Michael Cooper describes an anecdote involving Harrell and a bust-up at the MCA Records Conference in Midtown Manhattan that demonstrates how Harrell employed street enforcers and drug dealers at Uptown, and that they even procured him a gun for protection:

There was a rumor going around the streets of New York that Teddy’s manager, former drug dealer and karate enthusiast Gene Griffin, had smacked Andre in the conference of MCA Records in Midtown Manhattan. Journalist and author Nelson George, gave me Andre’s telephone number, so I could confirm the story. I called Andre and identified myself, and asked him about the confrontation with Griffin. I also asked him about the story of two of his Uptown Record executives—Jimmy “Luv” Jenkins and George Harrell (no relation), two of the most respected street dudes from the Highbridge neighborhood of the Bronx, and 116th Street in Harlem, respectively—giving him a .45 automatic to keep for protection. Andre tried to place the gun in the back of his waistband. However, the .45 slipped through and down his pants, and landed on the floor of the elevator. Andre, Jimmy, and George jumped back, but the gun didn’t discharge. Andre didn’t respond for almost a minute, and then said to me, “Who are you supposed to be? Ed Bradley? Things happen.” We cracked up laughing, and became fast friends after that.

In addition to MCA being critical to Harrell’s career and MCA’s success, Uptown’s relationship with MCA also appears to align with one of Combs’ earliest known sex crimes. For instance, one of the earliest allegations against Combs asserts that Combs sexually assaulted a victim after an MCA event in New York in 1990 or 1991, a time when Combs was still an Uptown employee.

As Strictly Business scriptwriter Nelson George intimated in a Substack post eulogizing his friend Andre Harrell, Harrell was a known “party animal” who frequently threw house parties in the “work space/social club/temporary housing” that served as the nascent Uptown Records’ offices. In fact, one of these parties in 1990 served as the source of inspiration for Strictly Business, the film that George co-wrote with Pam Gibson and which Andre Harrell executive produced for Island World Pictures (a company then affiliated with Polygram, which took a significant stake in Def Jam in 1992). It was Harrell’s role in the film that reportedly led MCA to enter into its $50 million multimedia deal with Uptown in 1992 that saw Harrell’s company expand into film. Strictly Business concerns a young mail room clerk setting up a black middle manager at a real estate firm with a club chick played by the emerging starlet Halle Berry. Bobby the mail clerk is a party boy with aspirations of graduating from the trainee broker program, and so he agrees to help Waymon navigate seducing the attractive woman in return for his higher-up’s sponsorship of his candidacy. While the plot may seem like normal rom-com fare and relatively benign, when viewed within the context of the kinds of sexual quid pro quos that occur within the music industry and Harrell’s close ties to figures like Combs, Simmons, and their broader social networks, it starts to take on a distinctly different slant. Speaking of sexual quid pro quos in the music industry and questionable label romances, Andre Harrell left an indelible influence on Combs’ love life. He hired Uptown R&B singer Al B. Sure’s model girlfriend Kim Porter to work as a receptionist at the label. Combs’ was immediately smitten with her, loving what he couldn’t have. They would go on to have an on-and-off again relationship spanning the years from 1994 to 2018, the time of her mysterious death after contracting a virulent case of lobar pneumonia. We will return to Porter and Combs’ ties to the modeling industry in Part III of this series.

Andre Harrell was also a consultant for the film New Jack City. New Jack City’s screenwriter Barry Michael Cooper recalls how he and producer George Jackson called his close friend Andre Harrell into Robert De Niro’s Tribeca Productions compound to watch the dailies from New Jack City a week before production wrapped. Cooper and Jackson wanted to gauge Andre Harrell’s reaction to New Jack City’s narrative and the depictions of street life as it related to the crack epidemic. Per Cooper’s retelling, apparently Harrell raved and affectionately called the film “The Black Godfather.”

New Jack City’s narrative revolves around a Harlem gang called the Cash Money Brothers who ascend to the top of the drug-dealing food chain in the borough once crack cocaine is introduced to the streets. The film featured gangster rap mainstay Ice-T in a prominent role and christened the careers of Wesley Snipes and Chris Rock, seeing a healthy return of nearly $50 million on a budget of $8 million.

The controversial film was developed by Warner Brothers, which was then run by Steve Ross. Ross was able to build up his business empire, Kinney National Company (which later became Warner), largely through his association with New York crime lords Manny Kimmel and Abner “Longy” Zwillman. Zwillman was a close associate of Meyer Lansky and Sam Bronfman. Ross, as a Warner executive, later frequented Robert Maxwell’s yacht in the late 1980s, a time when Maxwell was deeply associated with a litany of organized crime figures across the globe. In addition, top Warner executives close to Ross personally were convicted for their roles in a mob-tied racketeering scheme that was also allegedly involved Ross, though he somehow evaded charges.

Considering his informal consultation on the film and the fact that Harrell had underwritten “new jack swing” — Uptown’s claim to fame and the genre from which the film took its name, which fused streetwise hip hop beats and melodic R&B for the first time — Harrell’s influence over the New Jack City production is clear. This is an important point, as it relates to mob-linked entertainment companies (in this case Warner Brothers) financing the glorification of drug dealing around 1991, a topic that we will return to in much greater detail near the end of this piece.